রোমান্স ভাষাসমূহ

এই নিবন্ধটি ইংরেজি থেকে বাংলায় অনুবাদ করা প্রয়োজন। এই নিবন্ধটি ইংরেজি ভাষায় লেখা হয়েছে। নিবন্ধটি যদি ইংরেজি ভাষার ব্যবহারকারীদের উদ্দেশ্যে লেখা হয়ে থাকে তবে, অনুগ্রহ করে নিবন্ধটি ঐ নির্দিষ্ট ভাষার উইকিপিডিয়াতে তৈরি করুন। অন্যান্য ভাষার উইকিপিডিয়ার তালিকা দেখুন এখানে। এই নিবন্ধটি পড়ার জন্য আপনি গুগল অনুবাদ ব্যবহার করতে পারেন। কিন্তু এ ধরনের স্বয়ংক্রিয় সরঞ্জাম দ্বারা অনুবাদকৃত লেখা উইকিপিডিয়াতে সংযোজন করবেন না, কারণ সাধারণত এই সরঞ্জামগুলোর অনুবাদ মানসম্পন্ন হয় না। |

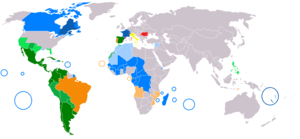

রোমান্স ভাষাসমূহ (ইংরেজি: Romance languages বা Romanic languages) ইন্দো-ইউরোপীয় ভাষা-পরিবারের একটি শাখা। রোমান সাম্রাজ্যের ভাষা লাতিন থেকে উদ্ভূত সবগুলি ভাষা এই ভাষা-পরিবারের অন্তর্গত। এই ভাষাগুলিতে উত্তর আমেরিকা, দক্ষিণ আমেরিকা, ইউরোপ, আফ্রিকা ও বিশ্বের বিচ্ছিন্ন কিছু ক্ষুদ্র অঞ্চলে প্রায় ৭০ কোটি মানুষ কথা বলে থাকে।

| রোমান্স | |

|---|---|

| ভৌগোলিক বিস্তার |  |

| ভাষাগত শ্রেণীবিভাগ | ইন্দো-ইউরোপীয়

|

| উপবিভাগ | |

| আইএসও ৬৩৯-২/৫ | roa |

সবগুলি রোমান্স ভাষা প্রাকৃত লাতিন ভাষা (Vulgar Latin) থেকে উৎপত্তি লাভ করেছে। রোমান সাম্রাজ্যের সেনা, বণিক, ব্যবসায়ী ও সাধারণ লোকালয়ের মানুষেরা এই প্রাকৃত লাতিন ভাষায় কথা বলত। প্রাকৃত লাতিন ছিল ধ্রুপদী লাতিন থেকে বেশ আলাদা। ২০০ খ্রিস্টপূর্বাব্দ থেকে ১৫০ খ্রিস্টাব্দের মধ্যবর্তী সময়ে রোমান সাম্রাজ্যের ব্যাপক বিস্তার ঘটে এবং এসময় পূর্বে কৃষ্ণ সাগর থেকে পশ্চিমে আইবেরীয় উপদ্বীপ, উত্তরে ব্রিটিশ দ্বীপপুঞ্জ থেকে দক্ষিণে উত্তর আফ্রিকা পর্যন্ত এক বিশাল এলাকা জুড়ে সাম্রাজ্যের প্রশাসনিক ও শিক্ষামাধ্যমের ভাষা হিসেবে লাতিন আধিপত্য বিস্তার করে। ৫ম শতাব্দীতে রোমান সাম্রাজ্যের পতনের পর স্থানীয় লোকালয়গুলিতে লাতিনের বিভিন্ন উপভাষাগুলি দ্রুত বিবর্তিত হতে থাকে এবং বহু অসংখ্য স্থানীয় ভাষার জন্ম দেয়। এদেরই কিয়দংশ বর্তমান আধুনিক রোমান্স ভাষা হিসেবে টিকে আছে। ১৫শ শতকের পর স্পেন, ফ্রান্স ও পর্তুগাল বিশ্বের অন্যত্র উপনিবেশ স্থাপন করায় এই ভাষাগুলি ইউরোপের বাইরে অন্যান্য মহাদেশে ছড়িয়ে পড়ে। বর্তমানে রোমান্স ভাষাভাষী ৭০% লোকই ইউরোপের বাইরে বসবাস করে।

প্রাক-রোমান ভাষার প্রভাব ও পরবর্তীকালে অন্যান্য ভাষার আক্রমণ সত্ত্বেও সবগুলি রোমান্স ভাষার ধ্বনিতত্ত্ব, রূপমূলতত্ত্ব, শব্দভাণ্ডার, ও বাক্যতত্ত্ব মূলত লাতিন ভাষার বিবর্তিত রূপ। ফলে ভাষাগুলি এমন কিছু ভাষাতাত্ত্বিক বৈশিষ্ট্য অর্জন করেছে, যা এদেরকে অন্যান্য ইন্দো-ইউরোপীয় ভাষা থেকে আলাদা করে রেখেছে। দুই-একটি ব্যতিক্রম ছাড়া সবগুলি রোমান্স ভাষাই ধ্রুপদী লাতিনের declension বা নামশব্দের রূপভেদ ব্যবস্থা বর্জন করেছে। সবগুলি রোমান্স ভাষাই কর্তা-ক্রিয়া-কর্ম এই বাক্য গঠন অনুসরণ করে, এবং ব্যাপকভাবে পুরঃসর্গ বা preposition ব্যবহার করে।

নাম সম্পাদনা

রোমান্স "Romance" নামটি প্রাকৃত লাতিন ক্রিয়াবিশেষণ romanice থেকে এসেছে, যেটি আবার ধ্রুপদী লাতিনের romanicus (রোমানিকুস) শব্দ থেকে বিবর্তিত।

রোমান্স বা রোমান্টিক উপন্যাসে ব্যবহৃত রোমান্স শব্দটির ব্যুৎপত্তিও একই। মধ্যযুগে ইউরোপে গুরুগম্ভীর রচনা মূলত লাতিনে লিখিত হত, আর সাধারণ জনগণের জনপ্রিয় প্রেমের কাহিনী ও অন্যান্য লঘু রচনাগুলি রচিত হত স্থানীয় প্রাকৃত ভাষায় রচিত হত এবং এগুলিকে রোমান্স বলে অভিহিত করা হত।

বর্তমান মর্যাদা সম্পাদনা

মাতৃভাষীর সংখ্যা অনুযায়ী সবচেয়ে বেশি প্রচলিত রোমান্স ভাষাগুলি হল স্পেনীয় ভাষা, পর্তুগিজ ভাষা, ফরাসি ভাষা, ইতালীয় ভাষা ও রোমানীয় ভাষা। এগুলির প্রতিটিই একাধিক রাষ্ট্রের প্রধান ও সরকারি ভাষা। এছাড়াও এটি সারদিনিয়ার সারদি

A few other languages have official status on a regional or otherwise limited level, for instance Friulian, Sardinian and Valdôtain in Italy; Romansh in Switzerland; Galician, Occitan Aranese and Catalan in Spain (the last of which is also the only official language in the small sovereign state of Andorra). French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and Romanian are also official languages of the European Union. Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, Romanian, and Catalan are the official languages of the Latin Union; French and Spanish are two of the six official languages of the United Nations.

Outside Europe, French, Spanish and Portuguese are spoken and enjoy official status in various countries that made up their respective colonial empires. French is an official language of Canada, Haiti, many countries in Africa, and some in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, as well as France's current overseas possession. Spanish is an official language of Mexico, much of South America, Central America and the Caribbean, and of Equatorial Guinea in Africa. Portuguese is the official language of Brazil, multiple countries in Africa and of East Timor. Although Italy also had some colonial possessions, its language did not remain official after the end of the colonial domination, resulting in Italian being spoken only as a minority or secondary language by immigrant communities in North and South America and Australia or African countries like Libya, Eritrea and Somalia. Romania did not establish a colonial empire, but the language spread outside of Europe due to emigration, notably in Western Asia; Romanian flourished in Israel, where it is spoken by some 5% of the total population as mother tongue,[১] and by many more as a secondary language, considering the large population of Romanian-born Jews who moved to Israel after World War II.[২]

The total native speakers of Romance languages is divided as follows (with their ranking within the languages of the world in brackets):

- Spanish 47% (5th)

- Portuguese 26% (7th)

- French 11% (11th)

- Italian 9% (18th)

- Romanian 4% (34th)

- Catalan 1% (n/a)

- others 2%

- Source: MSN Encarta – Languages Spoken by More Than 10 Million People ওয়েব্যাক মেশিনে আর্কাইভকৃত ৩ ডিসেম্বর ২০০৭ তারিখে (number of Romance speakers estimated at 690 million speakers, number of Catalan language speakers estimated at 8 million)

The remaining Romance languages survive mostly as spoken languages for informal contact. National governments have historically viewed linguistic diversity as an economic, administrative or military liability, as well a potential source of separatist movements; therefore, they have generally fought to eliminate it—by extensively promoting the use of the official language, by restricting the use of the "other" languages in the media, by characterizing them as mere "dialects"—or worse.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, however, increased sensitivity to the rights of minorities have allowed some of these languages to recover some of their prestige and lost rights. Yet, it is unclear whether these political changes will be enough to reverse the minority languages' decline.

Linguistic features সম্পাদনা

Features inherited from Indo-European সম্পাদনা

As members of the Indo-European (IE) family, Romance languages have a number of features that are shared with other members of this family, and in particular with English; but which set them apart from languages of other families, such as Arabic, Basque, Hungarian, or Georgian. These include:

- Almost all their words are classified into four major classes — nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs — each with a specific set of possible syntactic roles.

- Nouns, adjectives, determiners and some pronouns inflect according to grammatical number and grammatical gender.

- Inflection is normally marked with suffixes.

- A variety of grammatical distinctions are expressed on verbs, such as:

- They are verb-centered; meaning that the basic clause structure consists of a verb, expressing an action involving one or more nouns — the arguments of the verb — that play specific semantic roles in the action and specific syntactic roles in the clause.

- They are fusional, nominative-accusative languages.

Features inherited from Classical Latin সম্পাদনা

The Romance languages share a number of features that were inherited from Classical Latin, and collectively set them apart from most other Indo-European languages.

- They have two grammatical numbers, singular and plural (no dual).

- In most languages, personal pronouns have different forms according to their grammatical function in a sentence (a remnant of the Latin case system); there is usually a form for the subject (inherited from the Latin nominative) another for the object (from the accusative or the dative), and a third set of personal pronouns used after prepositions or in stressed positions (see Prepositional pronoun and Disjunctive pronoun, for further information). Third person pronouns often have different forms for the direct object (accusative), the indirect object (dative), and the reflexive.

- Most are null-subject languages. French is a notable exception.

- Verbs have many conjugations, including in most languages:

- A present tense, a preterite, an imperfect, a pluperfect and a future tense in the indicative mood, for statements of fact.

- Present and preterite subjunctive tenses, for hypothetical or uncertain conditions. Several languages (for example, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish) have also imperfect and pluperfect subjunctives.

- An imperative mood, for direct commands.

- Three non-finite forms: infinitive, gerund, and past participle.

- Distinct active and passive voices, as well as an impersonal passive voice.

- The main tense and mood distinctions that were made in classical Latin are generally still present in the modern Romance languages, though many are now expressed through compound rather than simple verbs. The passive voice, which was mostly made up of simple verbs in classical Latin, was completely replaced with compound forms.

- Several tenses, especially of the indicative mood, have been preserved with little change:

| Present | Preterite | Imperfect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin | dīcit | dīxit | dicēbat |

| Italian | dice | disse | diceva |

| Spanish | dice | dijo | decía |

| Sicilian | dici | dissi | dicìa |

| French | dit | dit | disait |

| Neapolitan | dice | dicette | diceva |

| Portuguese | diz | disse | dizia |

| Romanian | zice | zise | zicea |

| Galician | di | dixo | dicía |

| Catalan | diu | digué | deia |

| Piedmontese | a dis | a l'ha dit | a disìa |

| English | [he] says | [he] said | [he] used to say |

Features inherited from Vulgar Latin সম্পাদনা

Romance languages also have a number of features that are not shared with Classical Latin. Most of these features are thought to be inherited from Vulgar Latin. Even though the Romance languages are all derived from Latin, they are arguably much closer to each other than to their common ancestor, due to a core of common developments. The main difference is the loss of the case system of Classical Latin, an essential feature which allowed great freedom of word order, and has no counterpart in any Romance language except Romanian. In this regard, the distance between any modern Romance language and Latin is comparable to that between Modern English and Old English. While speakers of French, Italian or Spanish, for example, can quickly learn to see through the phonological changes reflected in spelling differences, and thus recognize many Latin words, they will often fail to understand the meaning of Latin sentences.

- The distinctions of vowel length present in Classical Latin were lost in most Romance languages (an exception is Friulian), and partly replaced with "qualitative" contrasts like monophthong versus diphthong (Italian, Spanish; French to a lesser extent), or with vowel height contrasts (as in Portuguese and Catalan).

- There are definite and indefinite articles, derived from Latin demonstratives and the numeral unus ("one").

- There are only two grammatical genders, masculine and feminine. The neuter gender of Latin has been lost (mostly merging with the masculine). (Exceptions: Romanian, which retains neuter gender; Spanish, which has the neuter third person pronoun ello, the neuter demonstratives eso, esto, aquello, and the neuter article lo, all used for objects or some abstract notions; and Italian, which while not keeping the neuter gender intact, has residual traces of it represented by some words that switch gender between singular and plural, such as il dito (the finger), plural le dita, inherited from Latin digitum, plural digita).

- Apart from gender and number, nouns, adjectives and determiners are not inflected. Cases have generally been lost, though a trace of them survives in the personal pronouns. An exception is Romanian, which retains a combined genitive-dative case.

- Adjectives generally follow the noun they modify.

- Many Latin combining prefixes were incorporated in the lexicon as new roots and verb stems, e.g. Italian estrarre ("to extract") from Latin ex- ("out") and trahere ("to drag").

- Many Latin constructions involving nominalized verbal forms (e.g. the use of accusative plus infinitive in indirect discourse and the use of the ablative absolute) were dropped in favor of constructions with subordinate clauses in all Romance languages except Italian (for example, Latin tempore permittente > Italian tempo permettendo; L. hoc facto > I. fatto ciò).

- The normal clause structure is SVO, rather than SOV, and is much less flexible than in Latin.

- Due to sound changes which made it homophonous with the preterite, the Latin future indicative tense was dropped, and replaced with a periphrasis of the form infinitive + present tense of habēre ("to have"). With time, this structure was reanalysed as a new future tense.

- In a similar process, an entirely new tense conditional form was created.

- While the synthetic passive voice of classical Latin was abandoned in favour of periphrastic constructions, the active voice remained in use. However, several tenses have changed meaning, especially subjunctives. For example:

- The Latin pluperfect indicative became a conditional in Catalan and Sicilian, and an imperfect subjunctive in Spanish.

- The Latin pluperfect subjunctive developed into an imperfect subjunctive in all languages except Romansh, where it became a conditional, and Romanian, where it became a pluperfect indicative.

- The Latin preterite subjunctive, together with the future perfect indicative, became a future subjunctive in Old Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician.

- The Latin imperfect subjunctive became a personal infinitive in Portuguese and Galician.

- Many Romance languages have two copular verbs, derived from the Latin stare (mostly used for "temporary state") and esse (mostly used for "essential attributes"). However, the distinction was eventually lost in some languages, notably French, which now have only the first copula. In French, stare and esse had become ester and estre by the late Middle Ages. Due to phonological development, there were the forms êter and être, which eventually merged to être. In Italian, the two verbs share the same past participle, stato. See Romance copula, for further information.

সম্পাদনা

The Romance languages also share a number of features that were not the result of common inheritance, but rather of various cultural diffusion processes in the Middle Ages — such as literary diffusion, commercial and military interactions, political domination, influence of the Catholic Church, and (especially in later times) conscious attempts to "purify" the languages by reference to Classical Latin. Some of those features have in fact spread to other non-Romance (and even non-Indo-European) languages, chiefly in Europe. Here are some of these "late origin" shared features:

- Most Romance languages have polite forms of address that change the person and/or number of 2nd person subjects (T-V distinction), such as the tu/vous contrast in French, the tu/Lei contrast in Italian, the tu/dumneavoastră (from dominus + vostre) in Romanian or the tú (or vos)/usted contrast in Spanish.

- They all have a large collection of learned Hellenisms and Latinisms, with prefixes, stems, and suffixes retained or reintroduced from Greek and Latin, and used to coin new words. Most of these are also used in English, e.g. tele-, poly-, meta-, pseudo-, dis-, ex-, post-, -scope, -logy, -tion.

- During the Renaissance, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and a few other Romance languages developed a new, progressive aspect that did not exist in Latin. In French, progressive constructions remain very limited, the imperfect aspect generally being preferred, as in Latin.

- Many Romance languages now have a verbal construction analogous to the present perfect of English. In some, it has taken the place of the old preterite (at least in the vernacular); in others, the two coexist with somewhat different meanings.

Divergent features সম্পাদনা

In spite of their common origin, the descendants of Vulgar Latin have many differences. These occur at all levels, including the sound systems, the orthography, the nominal, verbal, and adjectival inflections, the auxiliary verbs and the semantics of verbal tenses, the function words, the rules for subordinate clauses, and, especially, in their vocabularies. While most of those differences are clearly due to independent development after the breakup of the Roman Empire (including invasions and cultural exchanges), one must also consider the influence of prior languages in territories of Latin Europe that fell under Roman rule, and possible inhomogeneities in Vulgar Latin itself.

It is often said that French and Portuguese are the most innovative of the Romance languages, each in different ways, that Sardinian and Romanian are the most isolated and conservative variants, and that the languages of Italy other than Sardinian (including Italian) occupy a middle ground.[তথ্যসূত্র প্রয়োজন] Some even claim that Languedocian Occitan is the "most average" western Romance language. However, these evaluations are largely subjective, as they depend on how much weight one assigns to specific features. In fact all Romance languages, including Sardinian and Romanian, are all vastly different from their common ancestor.

Romanian (together with other related minor languages, like Aromanian) in fact has a number of grammatical features which are unique within Romance, but are shared with other non-Romance languages of the Balkans, such as Albanian, Bulgarian, Greek, Serbian and Turkish. These include, for example, the structure of the vestigial case system, the placement of articles as suffixes of the nouns (cer = "sky", cerul = "the sky"), and several more. This phenomenon, called the Balkan linguistic union, may be due to contacts between those languages in post-Roman times.

Sound changes সম্পাদনা

The vocabularies of Romance languages have undergone considerable change since their birth, by various phonological processes that were characteristic of each language. Those changes applied more or less systematically to all words, but were often conditioned by the sound context or morphological structure.

Some languages have lost sounds from the original Latin words. French, in particular, has dropped all final vowels, and sometimes also the preceding consonant: thus Latin lupus and luna became Italian lupo and luna but French loup [lu] and lune [lyn]. Catalan, Occitan, many Northern Italian dialects, and Romanian (Daco-Romanian) lost the final vowels in most masculine nouns and adjectives, but retained them in the feminine. Other languages, including Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and the Southern dialects of Romanian have retained those vowels.

Some languages have lost the final vowel -e from verbal infinitives, e.g. dīcere → Portuguese dizer ("to say"). Other common cases of final truncation are the verbal endings, e.g. Latin amāt → Italian ama ("he loves"), amābam → amavo ("I loved"), amābat → amava ("he loved"), amābatis → amavate ("you (pl.) loved"), etc.

Sounds have often been lost in the middle of words, too; e.g. Latin Luna → Galician and Portuguese Lua, crēdere → Spanish creer ("to believe").

On the other hand, some languages have inserted many epenthetic vowels in certain contexts. For instance Spanish, Galician and Portuguese have generally inserted an e at the start of Latin words that began with s + consonant, such as sperō → espero ("I hope"). French originally did the same, but then dropped the s: spatula → arch. espaule → épaule ("shoulder"). In the case of Italian, a unique article, lo for the definite and uno for the indefinite, is used for masculine s + consonant words (sbaglio, "mistake"), as well as all masculine words beginning with z (zaino, "backpack").

For more detailed descriptions, see the articles History of French, From Latin to Portuguese, Latin to Romanian sound changes, and Linguistic history of Spanish.

Lexical stress সম্পাদনা

The position of the stressed syllable in a word generally varies from word to word in each Romance language, and often moves as the word is inflected. Sometimes the stress is lexically significant, e.g. Italian Papa [ˈpa.pa] ("Pope") and papà [pa.ˈpa] ("daddy"), or Spanish imperfect subjunctive cantara ("[if he] sang") and future cantará ("he will sing"). However, the main function of Romance stress in appears to be a clue for speech segmentation — namely to help the listener identify the word boundaries in normal speech, where inter-word spaces are usually absent.

In Romance languages, the stress is usually confined to one of the last three syllables of the word. That limit may be occasionally exceeded by some verbs with attached clitics, e.g. Italian mettiamocene [me.ˈtːja.mo.ʧe.ne] or Metintilu in Friulian ("let's put some of it in there"), Spanish entregándomelo [en.tre.ɣan.do.me.lo] ("delivering it to me") or Portuguese dávamo-vo-lo ['da.vɐ.mu.vu.lu] ("we were giving it to you"). Originally the stress was predominantly in the penultimate syllable, but that pattern has changed considerably in some languages. In French, for instance, the loss of final vowels has left the stress almost exclusively on the last syllable.

Formation of plurals সম্পাদনা

Some Romance languages form plurals by adding /s/ (derived from the plural of the Latin accusative case), while others form the plural by changing the final vowel (by influence of the Latin nominative ending /i/).

- Vowel change: Italian, Romanian.

- Plural in /s/: Portuguese, Galician, Spanish, Catalan, Occitan, Sardinian, Friulian, Romansh.

- Special case of French: Falls into the second group historically (and orthographically), but the final -s is no longer pronounced (except in liaison contexts), meaning that singular and plural nouns are usually homophonous in isolation. Many determiners have a distinct plural formed by changing the vowel and allowing /z/ in liaison.

Borrowed words সম্পাদনা

টেমপ্লেট:Stub-section Vulgar Latin borrowed many words, often from Germanic languages that replaced words from Classical Latin during the Migration Period, even including common basic vocabulary. Notable examples are *blancus (white), which replaced Classical Latin albus in most major languages and dialects except for Romanian; *guerra (war), which replaced bellum; and words for the cardinal directions, where words similar to English north, south, east and west replaced the Classical Latin words borealis (or septentrionalis) (north), australis (or meridionalis) (south), occidentalis (west) and orientalis (east) everywhere (for standard usage). See History of French – The Franks.

Derivations সম্পাদনা

Words for "more" সম্পাদনা

Some Romance languages use a version of Latin plus, others a version of magis.

- Plus-derived: Sardinian prusu, French plus /ply/, Italian più /pju/, Friulian plui, Romansh pli, Venetina pi. In Catalan pus /pus/ is exclusively used on negative statements in Mallorcan Catalan dialect, and "més" is the word mostly used.

- Magis-derived: Sardinian (mera), Galician and Portuguese (mais; mediaeval Galician-Portuguese had both words: mais and chus), Spanish (más), Catalan (més), Venetian (massa or masa, "too much") Occitan (mai), Romanian (mai), Italian (mai, used in constructions such as non... mai, meaning "never", or "Londra è la più grande città che io abbia mai visto" "London is the biggest city I have ever seen").

Words for "nothing" সম্পাদনা

Although the Latin word for "nothing" is nihil, the common word for "nothing" became nudha in Sardinian, nada in Spanish and Portuguese, nada and ren in Galician, rien in French, res in Catalan, cosa and res in Aragonese, ren in Occitan, nimic in Romanian, and niente and nulla in Italian, gnente in Venetian, and nue and nuie in Friulian. Some argue that all three roots derive from different parts of a Latin phrase nullam rem natam ("no thing born"), an emphatic idiom for "nothing". Meanwhile, Italian and Venetian niente and gnente would seem to be more logically derived from Latin ne(c) entem ("no being").

The number 16 সম্পাদনা

Romanian constructs the names of the numbers 11–19 by a regular pattern which could be translated as "one-over-ten", "two-over-ten", etc.. All the other Romance languages use a pattern like "one-ten", "two-ten", etc. for 11–15, and the pattern "ten-and-seven, "ten-and-eight", "ten-and-nine" for 17–19. For 16, however, they split into two groups: some use "six-ten", some use "ten-and-six":

- "Sixteen": Catalan and Occitan setze, French seize, Italian sedici, Venetian sédexe, Romansh sedesch, Friulian sedis, Lombard sedas / sedes, Franco-Provençal sèze, Sardinian sédichi.

- "Ten and six": Portuguese dezasseis or dezesseis, Galician dezaseis, Spanish dieciséis, the Marchigiano dialect digissei.

- "Six over ten": Romanian șaisprezece (where spre derives from Latin super).

Classical Latin uses the "one-ten" pattern for 11–17 (ūndecim, duodecim, …, septendecim), but then switches to "two-off-twenty" (duodēvigintī) and "one-off-twenty" (ūndēvigintī). For the sake of comparison, note that English and German use two special words derived from "one left over" and "two left over" for 11 and 12, then the pattern "three-ten", "four-ten", …, "nine-ten" for 13–19.

To have and to hold সম্পাদনা

The verbs derived from Latin habēre "to have", tenēre "to hold", and esse "to be" are used differently in the various Romance languages, to express possession, to construct perfect tenses, and to make existential statements ("there is"). If we use T for tenēre, H for habēre, and E for esse, we have the following distribution:

- HHE: Romanian, Italian

- HHH: Occitan, French, Romansh.

- THH: Spanish, Catalan, Aragonese.

- TTH: European Portuguese.

- TTT: Brazilian Portuguese. (colloquial)

For example:

- English: I have, I have done, there is (HHE)

- Friulian: (jo) o ai, (jo) o ai fat, a 'nd è, al è (HHE)

- Venetian: (mi) go, (mi) go fat, ghe xe, ghi n'é (HHE)

- Lombard (Western): (mi) a gh-u, (mi) a u fai, al gh'è, a gh'è (HHE)

- Romansh: (jau) hai, (jau) hai fatg, igl ha (HHH)

- Romanian: (eu) am, (eu) am făcut, este (or e) (HHE)

- Italian: (io) ho, (io) ho fatto, c'è (HHE)

- French: j'ai, j'ai fait, il y a (HHH)

- Catalan: (jo) tinc, (jo) he fet, hi ha (THH)

- Aragonese: (yo) tiengo (but (yo) he dialectally), (yo) he feito, bi ha (THH)

- Spanish: (yo) tengo, (yo) he hecho, hay (THH)

- Galician: (eu) teño, - , hai (T-H; Galician does not have a present perfect)

- Portuguese: (eu) tenho, (eu) tenho feito, há in Portugal (TTH) / tem in Brazil (TTT)

Ancient Galician-Portuguese used to employ the auxiliary H for permanent states, such as Eu hei um nome "I have a name" (i.e. for all my life), and T for non-permanent states Eu tenho um livro "I have a book" (i.e. perhaps not so tomorrow), but this construction is no longer used in modern Galician and Portuguese. Informal Brazilian Portuguese uses the T verb even in the existential sense, e.g. Tem água no copo "There is water in the glass". In most languages, the descendant of tenēre still has the sense of "to hold", as well, e.g. Italian tieni il libro, French tu tiens le livre, Catalan tens el llibre, Romanian ține cartea, Friulian Tu tu tegnis il libri "You're holding the book". In others, like Portuguese, this sense has been mostly lost, and a different verb is currently used for "to hold". Romansh uses, besides igl ha, the form i dat (literally: it gives), borrowed from German es gibt.

To have or to be সম্পাদনা

Some languages use their equivalent of "have" as an auxiliary verb to form the perfect forms (e. g. French passé composé) of all verbs; others use "be" for some verbs and "have" for others.

- "Have" only: Standard Catalan, Spanish, Romanian, Sicilian.

- "Have" and "be": Occitan, French, Italian, Romansh, some dialects of Catalan (although such usage is recessing in those).

In the latter, the verbs which use "be" as an auxiliary are unaccusative verbs, that is, intransitive verbs that show motion not directly initiated by the subject or changes of state, such as "fall", "come", "become". All other verbs (intransitive unergative verbs and all transitive verbs) use "have". For example, in French, J'ai vu "I have seen" vs. Je suis tombé "I am fallen" ("I have fallen"). A similar dichotomy exists in the Germanic languages, which share the same Sprachbund; German and the Scandinavian languages use "have" and "be", while modern English uses "have" only.

I did or I have done সম্পাদনা

Some languages (e.g. Spanish, Catalan, Occitan, Portuguese and written French and Italian) make a distinction between a preterite and a present perfect tense (cf. English I did vs. I have done). Others (spoken French, Italian and Galician) contain only one tense, which renders both meanings. French, Italian, and European Spanish use the compound past for this, while Sicilian and Latin American Spanish use the simple past.

Writing systems সম্পাদনা

The Romance languages have kept the writing system of Latin, adapting it to their evolution. One exception was Romanian before the 19th century, where, after the Roman retreat, literacy was reintroduced through the Romanian Cyrillic alphabet due to Slavic influences. Also the non-Christian populations of Spain used the systems of their culture languages (Arabic and Hebrew) to write aljamiado versions of Castilian (Ladino among Sephardic Jews).

Letter values সম্পাদনা

All Romance languages are written with the "core" Latin alphabet of 22 letters — A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, V, X, Y, Z — subsequently modified and augmented in various ways. In particular, the letters K and W are rarely used in most Romance languages — mostly for unassimilated foreign names and words, as they were in late Latin.

While most of the 22 basic Latin letters have maintained their phonetic value, for some of them it has diverged considerably; and the new letters added since the Middle Ages have been put to different uses in different scripts. Some letters, notably H and Q, have been variously combined in digraphs or trigraphs (see below) to represent phonetic phenomena not recorded in Latin, or to get around previously established spelling conventions.

A characteristic feature of the writing systems of almost all Romance languages is that the Latin letters C and G — which originally always represented /k/ and /g/ respectively — represent other sounds when they come before E, I, and in some cases Y and Œ. This is due to a general palatalization of /k/ and /ɡ/ before front vowels like /i/ and /e/. This is believed to have occurred in the transition from Classical to Vulgar Latin. Since the written form of all the affected words was tied to the classical language, the shift was accommodated by a change in the pronunciation rules. However, the new sounds of C and G in those contexts differ from language to language.

The spelling rules of most Romance languages are fairly complex, and subject to considerable regional variation. To a first approximation, the phonetic representation of non-combined letters can be summarized as follows:

- C: generally [k], but "softened" before E, I, or Y in most Romance languages — to [s] in French, Portuguese, Occitan, Catalan, and American Spanish; to [θ] in Peninsular Spanish and Galician; to [ts] in Romansh; and to [ʧ] in Italian and Romanian.

- G: generally [ɡ] or [ɣ], but "softened" before E, I, or Y in most languages — to [ʒ] in French, Portuguese, Occitan and Catalan; to [x] or [h] in Spanish (according to dialect); to [ɟ] in Romansh; and to [ʤ] in Italian and Romanian.

- H: silent in most languages, but represents [h] in Romanian and Gascon Occitan. Used in various digraphs (see below).

- J: represents [ʒ] in most languages; [x] or [h] in Spanish; [j] in Romansh and in several of Italy's languages, though it is normally replaced with I in native Italian words.

- S: normally represents [s] (either laminal or apical) at syllable onset, but usually [z] between vowels. Intervocalic s is, however, pronounced [s] in Spanish, Romanian, Galician and several varieties of Italian. In the syllable coda, it may have special allophonic pronunciations.

- W: used only in Walloon. Represents [v] in French, with the exception of words borrowed from English.

- X: at the beginning of words, represents [ks] (in some words [ɡz]) in French, [s] or [ks] in Spanish, and [ʃ] in Portuguese, Catalan, and Galician. In intervocalic position, represents [ks] in French, Portuguese, Spanish, and Romanian; [ɡz] in Catalan, French, and Romanian; [ɡs] in Galician and Spanish; [ʃ] in Catalan, Galician and Portuguese; [z] in Venetian, French and Portuguese; or [s] in French and Portuguese. Not used in Italian (except in borrowings), where it is replaced by s.

- Y: used in French and Spanish for the vowel [i], and also as a consonant, [j] (esp. in French), [ʝ], [ʒ] or [ʤ].

- Z: [z] in most languages; either [θ] or [s] in Galician and Spanish; either [ʣ] or [ʦ] in Italian.

Otherwise, letters that are not combined as digraphs generally have the same sounds as in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), whose design was, in fact, greatly influenced by the Romance spelling systems.

Digraphs and trigraphs সম্পাদনা

Since most Romance languages have more sounds than can be accommodated in the Roman Latin alphabet they all resort to the use of digraphs and trigraphs — combinations of two or three letters with a single sound value. The concept (but not the actual combinations) derives from Classical Latin; which used, for example, TH, PH, and CH when transliterating the Greek letters "θ", "ϕ" (later "φ"), and "χ" (These were once aspirated sounds in Greek before changing to corresponding fricatives and the <H> represented what sounded to the Romans like an /ʰ/ following /t/, /p/, and /k/ respectively. Some of the digraphs used in modern scripts are:

তথ্যসূত্র সম্পাদনা

- ↑ 1993 Statistical Abstract of Israel reports 250,000 speakers of Romanian in Israel, while the 1995 census puts the total figure of the Israeli population at 5,548,523

- ↑ "Reports of about 300,000 Jews who left the country after WW2"। ৩১ আগস্ট ২০০৬ তারিখে মূল থেকে আর্কাইভ করা। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২৩ সেপ্টেম্বর ২০০৭।